Flood

Two days ago I lay in the dark with no electricity or phone signal listening only to the sound of sirens and rain.

I say only. Both sounds were vivid and pulsating, unsettling and foreboding. And they continued all night. In the day it wasn’t so bad. Their noise was diminished by the grey glow of dawn but the night went on and on and on and I wondered what story they were telling.

It’s weird to be cut off, to be left adrift in the middle of a city, fingers instinctively tapping at light switches, grazing down darkening unresponsive phone and computer screens.

It takes a long time for morning to appear and when it does it is not with the bright chaos that normally accompanies it, a cacophony of alarms and cBeebies, kettles and toast. No, we get up and wait for the morning to come to us, huddled under a blanket as candles flicker, waiting for the dark of the sky to lighten, slowly so slowly lighten.

By seven am, we are desperate for something to happen, some news from the Outside. We live near the river and have no idea where it is and what has happened , how safe we are. My four year old and I get dressed haphazardly in the dark. I can’t find anything, spill tealight liquid and one Thomas the tank engine sock hugs tightly around my foot.

Outside is a relief, brighter and warmer than inside. I want to look at the river but my child is scared to. I have an idea that Wetherspoons will be open. It must be. Wetherspoons is always open. Wetherspoons can survive anything. We walk towards town in the expectation of lights and warmth.

Town is closed. Wetherspoons is closed. These are clearly the end times.

I never before knew how many noises alarms could make. There are sharp peeps, loud Whaas, stoppy starty screams, panicky bips all intermingling into a onslaught of Not Normal. It is still raining. You never normally notice how so many things are lit up- bus stops, shop signs, roads until they are gone.

The traffic lights are blank- I go to get cash out to be met with an impassive grey screen. I never thought of that.

My child is crying, desperate for somewhere to sit down, we are flotsam in a familiar yet unfamiliar environment, aliens. Home is not Home anymore, we keep walking- we are at the top of town, no idea of what lies at the bottom. I think of places that might have their own magical power supply that aren’t Wetherspoons and thus we head like cockroaches to the hospital.

It is not yet 8am.

I am annoyed at myself for getting so concerned. I have not seen any floods as yet and it might just be a power cut.

Then I see the army.

The army appear to doing Selfies outside the hospital which allays my fears somewhat especially as my first point of contact today is an elderly Lancastrian who tells me it ‘owt but a few puddles’.

Inside the hospital I parasitically charge up my phone expecting the whole generator to go off and a few thousand people to die as a result but an elderly lady tells me when I am being indecisive about this potential transgression that ‘you pay your taxes, love’ which convinces me. I am worryingly easy to convince.

The cafe opens and and a coffee and baked beans on toast has never been better. Then my child drops a bottle of Lucozade bottom down on the floor and my head erupts in surprisingly painful Lucozade lava. More NHS supplies and staff help me. I resolve never to moan about taxes again whilst leaving the hospital sticky and reeking of glucose with a Thomas the Tank Engine sock slowly cutting off all circulation in my right foot.

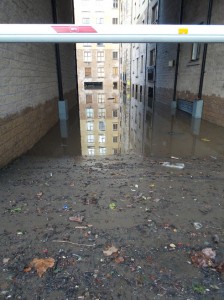

Lancaster is now full of zombies. I have never seen it so busy. With the absence of phones, people are sharing new rumours and gossip and queueing for public phone boxes. Every shop and cafe is closed and we head down to the bottom of town, our town to see it is pretty much afloat.

Abandoned cars with their numberplates dangling at unnatural angles, the insistent discordant squeal of a thousand alarms punctuating the air.

No-one is on their phones. Strangers stop to talk. There are water bottles for sale on trestle tables and a Samaritans van has a long long line of people who are not smiling and gossiping.

Everything familiar is unfamiliar. I want to take pictures but want my phone, my unresponsive phone to still retain its charge. I can’t believe how lost I feel without it.

The bus station is a river, the fire engine has a boat going down the road. Still people surge, never knew there were so many people in Lancaster. I see through windows of flooded student accommodation, people huddled in blankets in the rank mud of their living room.

I don’t want to go home. I like the safety of people, like hearing second hand the rumours ( ‘the power station is on fire,’ ‘Lancaster is an island’) the guilty sense of excitement.

Home is dark and cold and empty.

An enormous queue forms outside the one tiny corner shop open. It Is hard to believe how different things were yesterday.

But we are tired. We walk through a changed small city, a city where everyone is outside and where the alarms punctuate the cold air, a place of mud and water where Christmas and commerce seems to have suddenly vanished.

Then in the typical black hole of a formerly brightly lit establishment, the Robert Gillow we see candles. And hear music. We step inside into the black. A jazz band is playing lit by tea lights. A table is full of sandwiches and biscuits and at the bar, a man offers me warm beer or wine. He tells me not to bother about paying ‘as we are not counting pennies at a time like this, we just want to help people.’

I nearly cry. We sit in a corner and swap stories with strangers. My child drinks milk and smiles.

Outside, it is turning out to be a beautiful blue sky day.

Then I go home back to the dark and the unnatural noise of sirens, alarms and the river in my cellar.